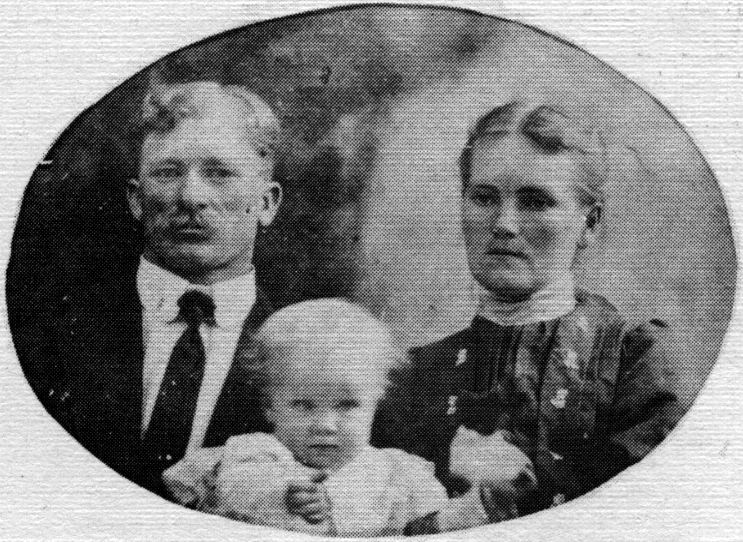

33 While I was still in Heaven, my cousins Iantha and Ianthus Campbell were born. Aunt Mary and Uncle Lew already had five girls and Iantha made six. But Ianthus was a boy! It's easy to guess how tickled Uncle Lew was about that. The twins arrived on August 10, 1909.

Mama and Papa had had four little girls, but my sister Josephine only stayed a little while, then returned to Heaven. That left Annie, who was six and one-half, Kate, not quite five, and the toddler, baby Mildred. Annie decided to ask the Heavenly Father to send twins to our family too. Kate also prayed for twins for awhile, then she decided Mama had enough girls, so she just asked for a little brother. Annie persisted in asking for twins. For eleven months she prayed. She has written:

Finally our prayers were answered! One night in mid July of 1910 when we went to bed, we said our prayers as usual, and when we awoke in the morning, the miracle had happened! Grandma was holding a tiny baby boy in her arms and there in the bed with my mother was a tiny baby girl. How wonderful! Words cannot express our joy. The Lord had answered our prayers by sending the desire of our hearts. Twins! We named them George and Alice for our grandparents. How we loved them!1

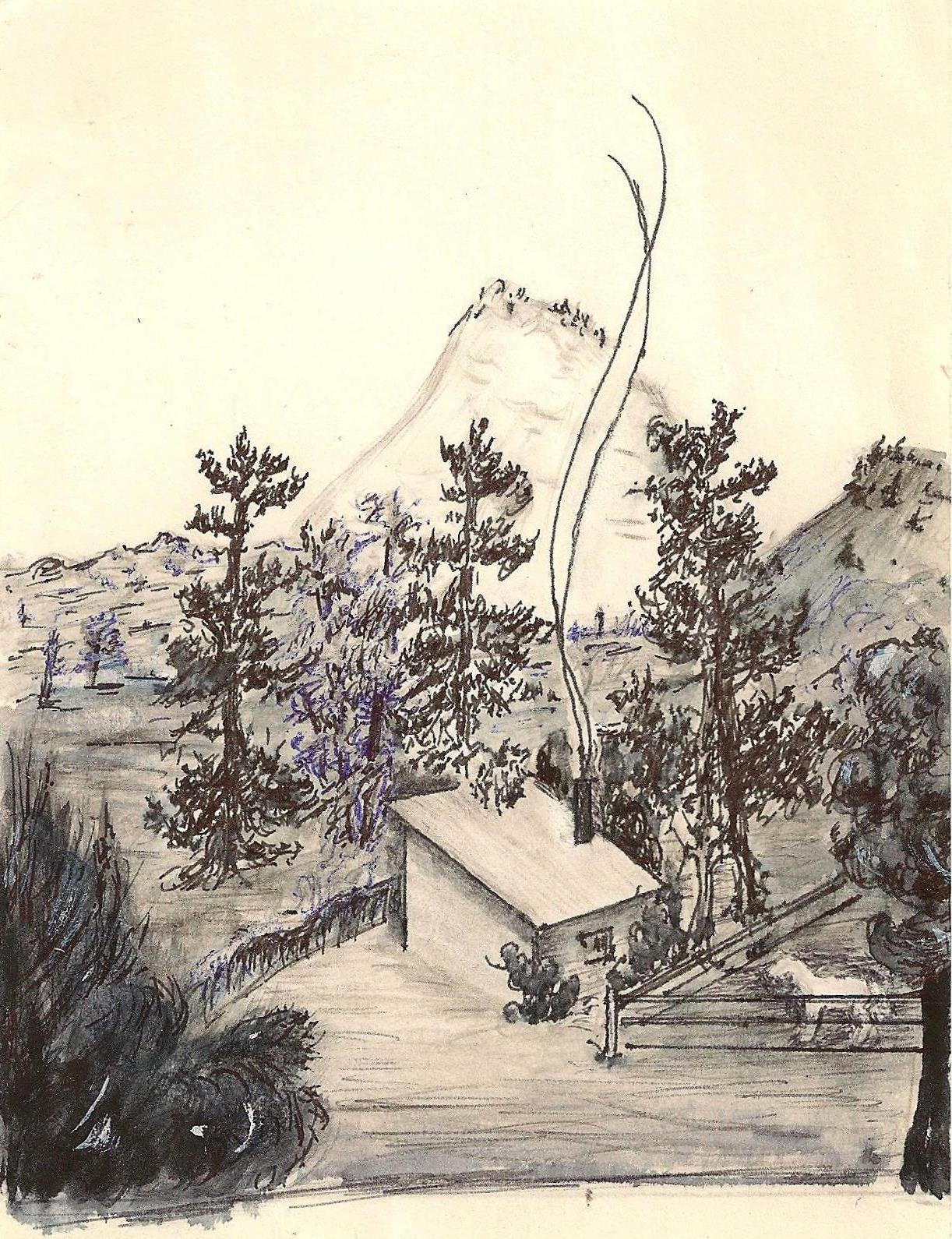

[Lower Kolob area, now a part of Zion National Park, Utah]

We arrived on July 17, 1910, on Aunt Ellen Spendlove's birthday, and on the anniversary of the landing of Noah's ark. (Genesis 8:4) We were born in a little lumber shack at the sawmill on Kolob. Grandma Isom was the doctor and the nurse.

According to an old Chinese tradition, if the first food a child ever tasted was baked apple, the child would become a fine singer. So Grandma baked an apple and scraped a little of it onto each of our tongues. I have no idea what my voice would have sounded like if it hadn't been for that.

My parents had been homesteading on Kolob since 1908, returning to Virgin in the winter time. Recorded in Mama's Memoirs is the following:

In 1911 we closed up the old home at Virgin and came direct from the mountain to Hurricane, where we had built a 12 X 14 granary but the babies took sick and being so cold and crowded, Alice and William Spendlove took us to their home where we could give them better care. … A week after we moved to Spendlove's, George died of inflammation of the bowels and was buried amid one of the most terrible north winds we have known. It was too severe for anyone to go to the graveyard except those that did the burying.

The Hurricane Canal froze over. Water, running over the ice, spilled down the banks, glazing the streets. Mama stayed with me, for I was not expected to live. My sisters wept. Annie remembers lying on the family bedrolls in Aunt Alice's living room, crying bitterly. She could not be comforted. Papa's heartbreak must have been great.

Is it possible that I remember my twin brother? It seems like I do. In my mind is a picture of another baby sitting with me on Papa's lap, while he sang a happy, nonsensical thing like "A chicken went to bed with the whooping cough." We both wore little white dresses. I have had an awareness of my brother George throughout my life, and I have grown to love him dearly.

44 The first five years of my life were my dominant ones. Kolob was Heaven to me. As soon as my sisters were out of school each spring we prepared to return to the ranch. The bustling of cooking and packing was a joyous time to me. I was surprised to learn years later, that the business of moving a family back and forth was just plain hard work for Mama.

We always camped at Sanders's Ranch on our way and one of Uncle Ren Spendlove's boys, either Whit, Ianthus or Cliff came along to help with the team. I loved camping out. I reveled in the smell and the squeak of harness leather and the clinking of buckles and the sounds of the wagon as it sighed and relaxed, cooling off in the night. Stretched out on the family bed spread on the ground, I listened to the horses munching grain in their nose bags, the gentle crackle of the dying campfire, and the stars, the millions of singing stars!

"Mama," I asked, "are all of the stars whirling? Is that what makes them sing?"

Mama listened thoughtfully, then she said, "No, the music you hear is made by the crickets and katydids and night birds in the bushes and trees, and by the water in the creek tumbling over pebbles."

I listened again and realized that the chirping and twittering and gurgling really was ascending up to instead of down from the stars.

Carlyle once said, "Give us, O give us the man who sings at his work. … The very stars are said to make harmony as they revolve in their spheres." The Prophet Job was informed that while the foundations of this earth were being laid "the morning stars sang together." Job 38:7

Well, the last morning star had scarcely faded when we broke camp and were on our way again. We had a long hill to climb before the sun got too hot for the horses. At Lamb Springs we ate breakfast and let the horses rest before their long hard pull through the sand.

We had to walk to lighten the load. I bawled because the sand burned my feet, still I pulled my coat around me.

"You're a ridiculous child," Mama remarked.

"But the wind is cold," I complained, then added, "If the trees would stop fanning then the wind could quit."

"The trees don't fan the wind," Mama explained, "the wind fans the trees."

"What a backwards situation," I thought.

With the deep sand behind us, back in the wagon we rode up around the cinder knoll and on past Mulligan's Point, to Maloney's Ranch and then to the Slick Rocks.

The Slick Rocks was the terrible test to the stubbornness of teamsters and the agonizing willingness of horse flesh. We gladly piled out of the wagon here. Vivid in my mind is the picture of Papa slapping the reigns on the horses' backs and yelling, "Git up Mag! Git up Dick!" Iron wagon tires screeched over steep red sandstone, horses strained muscle and sinew, pulling, pulling, leaning forward until they went to their knees. Terrified, I watched. Mag's and Dick's eyes glared wildly, their ears laid back. Sometimes the wagon started to slip back and Papa cracked the whip and yelled louder. The wagon could roll over the ledge on the right and all would be lost. With Papa's yelling and urging, the stout-hearted team made it over the bad spot, where, breathing hard and their hides shining with sweat, they stopped to rest before going on to the summit. The terror was over.

Photo by Aaron D. Gifford, taken spring 2010 near Alice's birthplace

55 We had made our safe return to Paradise, Kolob. My childhood Kolob was bluebells, wild roses and sego lilies. It was sandstone that could be rubbed into the shape of dolls, and pine bark, thick and soft for Cliff Spendlove to carve into toy horses. It was pollywogs in clear pools in the willows and water snakes that left narrow roads through our dugout playhouses in the sand banks. It was games in the twilight, scurrying through the soft sand and across the meadow calling, "barey ain't out today," while imagining the bear was crouching at the edge of the meadow behind the dark trees, ready to pounce upon us as we dashed into the house. It was the smell of pine and sage and oak, the cackle of the sage hen, the flicker of the bluebird and the hammering of the jay. It was the sight of Rube and Jody Maloney's sheep wagon with its bucket of sourdough hanging on the side, dough dripping down the wheels. It was the cheese house, cool and inviting where squirrels played tag through the rafters. It was the little brown wren that nested under the eaves. It was the crack of lightning and the clap of thunder and pine trees falling in a pillar of fire. It was the howl of the coyote. It was water rising in the damp sand where the shovel sought a water hole. It was Old Tiny, the dog, barking down the trail, bringing the last stray calf in at milking time. It was new milk guzzled from a tin cup at the corral gate, making a thick foam mustache across my upper lip. It was tall cool ferns packed around sweet pounds of butter ready to be sent to the store at Virgin. It was hot corn bread drenched with fresh butter at supper time, and the smell of lamp light on an oil cloth covered table. It was little new potatoes scrabbled from under the vine and sweet garden peas and juicy turnips. It was Paradise!

We moved from "Milwaukie," the sawmill canyon, to "Pinevalley", a mile or so on top, but we often hiked back. We would take a picnic and spend the day, where we gathered iron ore rocks eroded in the shape of peanuts, marbles and little dishes.

Elisha Lee's family came to celebrate one 4th of July with us. Papa put the alphogies2 on the saddle horse, with Edith in one leather pouch and I in the other. We rode around the mountain to the ice cave, where he filled the alphogies with ice. Edith and I rode back home in front of and behind the saddle with Papa. Mama made ice cream in gallon buckets that were set inside galvanized water buckets packed with ice and salt. The ice cream was turned back and forth by the bail. Every little while the lid was pried off the gallon bucket and the frozen cream scraped down from the sides with a knife, a drooling operation. There is nothing in all the world that compares with the ambrosia that came from that bucket.

Mama had a special No. 2 tub that she kept sterilized and shining for cheese making. The dairy thermometer, bobbing in the tub full of milk, fascinated me. I watched her stir in the rennet when the temperature was right, and with a long, thin bladed knife, cut the curd as it set, yellow puddles of whey separating as the curds became more solid. Hungrily we hung around. We loved curd, from the first soft white ones to the final squeaky yellow ones after the whey was drained and the coloring and salt added. Probably none of the cheese would have reached the press if Mama had doled out as much of it as we wanted. Still she was generous.

Now a part of Zion National Park, Utah

Photo by Aaron D. Gifford, October 2010

The cheese molds were made of pine slats held together with hoops. The press was a log, outside on the shady side of the house, rigged up for a lever. Mama lined the molds with cheesecloth and the sweet curd was packed inside and put under the press. We were eagerly on hand when she unmolded the cheese, for the pressure had 66 squeezed tantalizing little ruffles of it up around the edges of the mold. Patiently we waited as Mama trimmed these off, for we knew she would divide the .trimmings. among us. Next she rubbed the yellow discs of cheese with butter, smoothing and sealing the goodness in, then set them on the swinging shelf in the cheese house behind our cabin to cure.

Mama sometimes sent me to the sand wash with a little lard bucket to fetch water. We never wore shoes in the summertime and the sand often burned our feet. Once it was so hot that I cried. Mildred took her bucket and ran back and forth to the wash, burning her own bare feet to make a puddle path for me. I carried my bucket of water all the way to the house on the wet patches she had made, while she ran back to refill her bucket.

One sad little task was helping Papa take small animals from his traps while he held the steel jaws open with his foot. His hands were too crippled to set the traps, so that was our job too, while he supervised. I grieved for the woodchucks and gophers and other animals.

Uncle Ren Spendlove's boys took turns helping us. When they came from Hurricane they brought fresh fruit. During those years I never saw fruit that wasn't bruised from a rough wagon ride. I thought peaches and apples had to be bruised to be good. These were squashed, brown, oozy and delicious.

The big pine tree where our chicken coop was anchored was struck by lightening one night, which electrocuted our entire flock of chickens as they slept with their heads under their wings.

The only toys we knew were those we made. Our doll houses were dug into the sand bank with a spoon and decorated with lacy, sweet smelling Jerusalem Oak. The dolls were made of flowers with heads of the shiny black berries from the deadly nightshade. Our wagons were the bleached vertebrae of bones of animals found in the sand. Our miniature world was imaginative and happy.

I was five when the folks stopped going to the ranch. I was the one who closed the gate for the last time behind the wagon. In my hand I had a few tiny new potatoes the size of peas and one little golden cheese that had been pressed in a salt shaker lid. These small rations belonged to my rag doll family. I set them down at the foot of the big yellow pine that the gate was hinged on. After closing the gate, I climbed into the wagon. We were miles down the road before I remembered them. I felt badly. Two years later-when I went to Kolob with Aunt Ellen's family I looked, but there was no sign of them.

That was my last trip to Kolob as a child. All that remained to me were cherished memories. We used to climb the Hurricane hill often, my sisters and I, but we never turned around until we could see the white Kolob peaks and the Steamboat mountain. That was the goal of every hike.

My love for our Heavenly Father began at Kolob. I remember kneeling at Mama's knee as she helped me with my prayer. I felt warm and secure, knowing that even in the dark the Heavenly Father watched over me. This realization took the eeriness out of the shadows that moved outside the tent, and gave understanding to the noises of the night. Pine needles falling on canvas had the same lightness as the scampering of squirrel feet and the occasional thump of a falling cone sounded friendly as it rolled off the tent to the ground.

One day Mama let my sisters and me hike down to the sawmill canyon alone. We became so engrossed in gathering fancy rocks and wild flowers that time slipped away. The sun was settling into the grove to the west as we trudged 77 through sand and sage on the last stretch home.

With our arms full of treasures, we raced to the house to show Mama. The tantalizing smell of hot cornbread greeted us, for it was supper time. But the room was strangely empty. Mama was not there. I shot out the back door. Running to the tent where our beds were, I lifted the flap. The setting sun, filtering through canvas, filled the tent with a golden glow. There, kneeling beside her bed, was Mama. In astonished reverence, I waited.

"What were you doing?" I asked timidly as she arose.

"I was asking the Heavenly Father to bring my little girls safely home," she replied tenderly.

"I didn't know you could ask Him for things in the daytime," I marveled. I had supposed that aside from our regular family prayers, we prayed only before tumbling into our beds.

Sitting on the edge of her bed, Mama drew me to her. "We are our Heavenly Father's children," she said. "He loves us and will listen to us anytime."

It was all so clear. Father really meant father. I was really and truly His little girl, and I could call upon Him whenever I needed to! My heart was jubilant.3

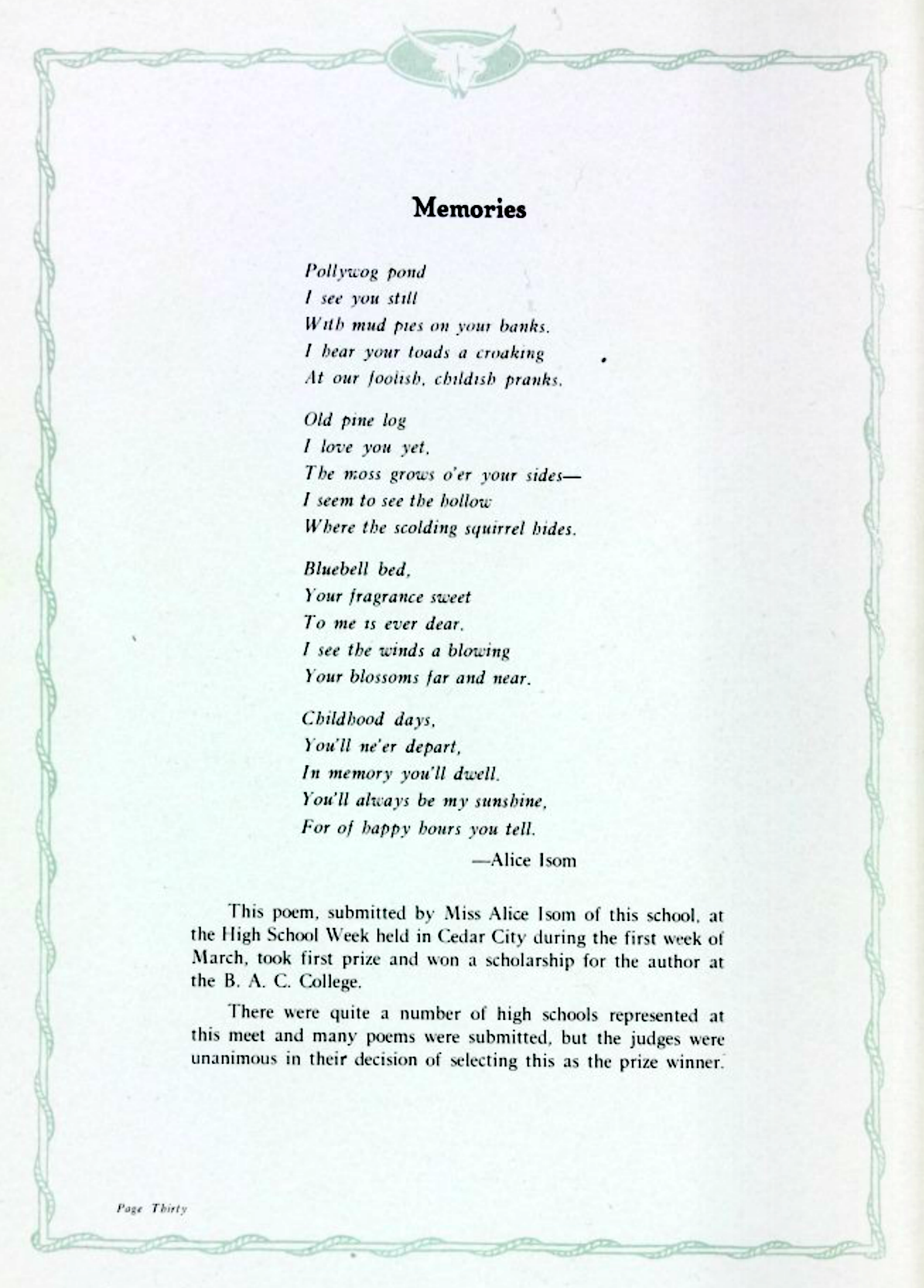

We not only draw spiritual dividends from childhood memories, but other blessings as well. As the composer has said .The song is ended, but the melody lingers on,. so Kolob memories are a melody to me.memories that paid my tuition for my first year in college.

In 1928, my English teacher, Mattie Ruesch, without my knowing it, entered one of my compositions in the lyric poem contest at the B.A.C. On College Day I was awarded the Spilsbury Memorial Scholarship for my—

Memories

Polliwog pond

I see you still

With mud pies on your banks.

I hear the toads a croaking

At our foolish, childish pranks.

Old pine log

I love you yet,

The moss grows o'er your sides—

I seem to see the hollow

Where the scolding squirrel hides.

Bluebell bed,

Your fragrance sweet

To me is ever dear.

I see the wind a blowing

Your blossoms far and near.

Childhood days,

You'll ne'er depart.

In memory you'll dwell.

You'll always be my sunshine,

For of happy hours you tell.

Footnotes

- Story "Double Blessing" published in Friend, May 1978, p. 2.

- Alphogies are leather pouches big enough to hold a child, that hang on each side of a pack horse.

- Story "Home Safe" published in Friend, September 1975, p. 48.