(1948)

213213 January 1. Resolved: I will consistently keep a journal this year.

February 1. The days pass me by. Who can actually keep a journal? But I haven't given up yet.

March 8. This morning, the hot water tank ran cold. The pilot light to the oil water heater had snuffed out again. The oil pan was flooded and I was scared. I looked across the field and saw Winferd in the top of a pear tree, pruning. I've got to stop being a baby, I thought, so I threw a lighted match into the puddle. A flame of fire leaped at me with a "boom, boom, boom," and the whole house shook.

Terrified, I ran out the door. "Winferd, Winferd!" I screamed.

He climbed down the ladder. I thought he had heard me, but he picked up his pruning saw, and climbed another tree. I screamed and screamed and he went on pruning. I ran back into the basement. The whole house roared, and the timbers under the bathroom floor were smoking.

Terry, Gordon and Shirley ran down the stairs. "Mother, mother, what's the matter?" they cried. When they saw the heater roaring and puffing, they cried harder. Shirley was supposed to be in bed sick.

"Go back to your bed, Shirley," I demanded. "Gordon, run across the field and get daddy quick, before the house burns down."

Gordon was so frightened he blubbered, "What's the matter! What's the matter!"

"Go," I demanded. "Go quick."

Howling, he stumbled across the field, looking back every little way. I couldn't wait for him. I raced across the square to the store. Like in a nightmare, I felt like I was running in one spot. Lyman Gubler met me at the door.

"Get someone quick that knows about oil heaters," I gasped, and ran back.

My lungs were bursting. I hurried into the basement and grabbed a quilt to beat out the flame, if necessary. The house was full of smoke, and the smell of burning pine. The pipes under the bathroom floor glowed red, and the heater boomed on.

Lyman dashed in, and turned everything there was to turn. "What's this?" he would ask, and give it a turn, and "what's this, and this?" Pointing to the little door to the oil pan, that was shooting fire, he asked, "What's this?"

"That's where I lit the flame. The house might blow up if you shut it."

He shut it anyway. It gave an anary white puff and began to subside. By this time, Winferd and Gordon arrived. Winferd opened the draft in the stove pipe, and the heater became still quieter, having spent itself.

214214 "Mother," Shirley shrieked. "Something is burning in the kitchen."

"Oh no," I groaned, running up the steps.

I had put milk on to scald so I could mix bread. The big coil had been left on high, and the upstair rooms were a black smudge that didn't smell as good as the pine smoke below. I put the charred remains out the door, then plopped onto the bed, pretty well spent. How utterly insignificant and helpless can a person be?

Mzrch 21. The first day of spring. Yellow crocus are blooming in the sun. Winferd, Marilyn, Norman and DeMar came home from quarterly conference thrilled, because they had shaken hands with our prophet, President George Albert Smith. He is here for the dedication of our new bishop's storehouse. Winferd will be away next Sunday, so we had our Easter dinner today. Gordon, Shirley and Terry scrubbed their hands, and from a bowl of mashed potatoes , molded bunnies and chickens to be browned in the oven. As they baked, Terry's rooster drooped his head, and one of the rabbits plopped over sidewise, but the rest were dandies. We had apricot upside down cake too. The family was thrilled with the Easter potatoes, and ate them in much less time than it took to fashion them.

After dinner, I looked with distress at the mountain of dirty dishes.

"Don't worry dear," Winferd said, "the wife is expected to work on Sunday."

"Is that so!" I retorted. "What about the second commandment?"

"Well, what about it

"The seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God. In it thou shalt not do any work," I quoted.

He raised an eyebrow. "Thou means the husband. It says, 'Thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter,' but it doesn't even mention 'thy wife,'" he teased.

I gulped. He grinned and put on his striped apron. He and the kids did the dishes, while I fed the baby.

March 22. Lolene coaxed for attention, but I wanted to finish my work, so I put the metronome on a chair beside her so she could watch it tick. She hushed. After awhile, I looked at her, and her eyes were going back and forth, back and forth with the ticker. She was hypnotized. I grabbed her in my arms to break the spell.

March 23. I patched eight pair of bib overalls today for Winferd, and darned his socks. He's going to be a wool jammer for Allie Stout's shearing crew.

March 24. I threw a scoop of slack coal onto the glowing coals in the furnace, then went upstairs. The kitchen door burst open and Gordon rushed in.

"Oh, Mother," he shouted, "you're scaring the Heavenly Father."

Going outside with him, I looked up. Well, I wouldn't wonder! From the chimney belched forth a billowing, black, smudgy cloud. In the still air, it spiraled up and up, looming like a monster above the roof.

215215 March 24. Winferd has gone to Paw Coon and I'm all alone—I and seven kids. And oh, groan—I've got the flu. I longed for just ten minutes to rest. The baby was asleep, the older kids in school, Gordon playing outside, and Terry peacefully playing with his blocks in the living room. I sagged onto the bed, and was just fading into oblivion, when Terry trotted in.

"I gotta use the toilet Alice. Get up and put on your shoes."

"Oh no," I sighed. "Terry is a big boy. You can go to the toilet all by yourself."

"Terry is too little. Come on Alice."

"Terry is big like daddy," I said hopefully.

There was an insistent tugging at my arm. His voice rose higher and higher. Then there were tears and a runny nose.

"Terry, while you're in the bathroom, wipe your nose too. My, but you're a good boy," I said.

"Ok," he said, and obediently trotted off to the bathroom.

A moment later, Gordon came in with a bent stick that went "bumpety, bumpety, bump," as he pushed it across the floor. Terry scrambled forth to admire it, then they both thought of bread and honey at the same time. Gordon decided that Terry couldn't have any. Terry shed loud tears.

"Gordon, let Terry have some honey," I called.

There was a spell of peace. I dozed. Then the walls of the bathroom 'vibrated.

"You can't drink in here, Terry," Gordon shrieked. "You're making the taps sticky."

Terry howled. Either my bones or the bed creaked as I got up to referee. By the time I reached the kitchen, those little monsters had gone outside and climbed a tree. The house was serene, but my nap time was over.

April 1. I iced an aluminum pan and decorated it like a cake for April Fool's dinner. Norman finished eating first, so I told him to cut the cake. He took his butter knife and sawed away.

Bewildered, he said, "It's kinds hard. I'd better get the bread knife."

"For silly," Marilyn said, "I can cut it." So she sawed away. "It's made of cement," she said, then she stood up, and with the point of her knife, bore her weight down in the middle of it.

Norman was back with the bread knife. After one attempt to cut the cake, he turned it over. The kids laughed heartily, then anused themselves peeling off the icing.

April 8. Marilyn put Norman's hair up in pin curls, and sent him off to bed with a hairnet on.

April 9. I asked Norman to go to the nursery and get some fruit trees to plant, then thought better of it, and asked him not to. So, tonight he came cheerfully home with eleven little trees. He and I chiseled in the red, hard clay to make holes big enough to spread out the roots.

216216 April 10. This morning, Arnold Cannon appeared at our door. "Aren't you glad I remembered your trees?" he greeted.

He had eleven more trees for us—a duplicate order. Oh, my aching back!

"We planted eleven trees yesterday," I explained, "but these look pretty nice. We'll take them anyway."

We chiseled out more holes and planted them. The trees sure look better than I feel.

April 11. Winferd arrived home, late and exhausted.

April 13. Winferd had to leave at 5:00 a.m. this Sunday morning. Some guys would break their necks to get in a full shift on Sunday. He didn't want to go. He loves the Sabbath day. But since he's the only wool jammer on this outfit, the shearers would be pretty mad if they were all forced to rest because of him. Well, they sheared 900 sheep, and the rain came and the sheep got wet, so the men came home. They don't have to be back until noon tomorrow.

April 14. How good it was to have Winferd home. He made me some headgates, and turned the water down, and killed that little speckled hen that's always getting out. I've hauled loads of ashes and dirt, building a dike around the run fence to outsmart that little bobtailed chicken.

Winferd kissed me goodbye, and I'm so lonesome I could die!

April 15. I thought only cats had nine lives. There is still a little bobtailed, speckled hen scratching in my garden! I'm plugging up more holes with ashes and dirt.

April 16. DeMar turned a nest of bagworms loose in the basement. I detest seeing a catepillar ambling down the steps ahead of me. DeMar is supposed to have cleaned them all out, but he isn't too thorough.

I promised the kids lemon chiffon pudding for supper if they'd set out four rows of strawberries after school. Norman played until 6:00 o'clock, then busted a tug to set out his two rows. DeMar played until seven, then dug his plants just at dusk. I made the pudding, but DeMar was still digging when there was no light in the sky but a scrap of a moon. I called him in and gave him a lecture. He promised to set his plants out before breakfast, if I wouldn't send him to bed without supper. All night long my subconscious nagged at me to get up, so he could fulfill his part of the bargain. He has finished and gone to school. The disciplining was harder on me than on him.

April 19. DeMar invited thirteen boys and DeLynn Woodbury to his birthday party. She sat on the front porch and played jacks , while the boys imagined they were airplanes. They swarmed through the trees and all over the back yard, making queer noises.

"DeMar," I said, calling him in, "before you pass the cookies, you should play just one honest game."

"Hey fellers," he called, "come here. We're going to play post-office."

DeLynn dashed frantically to my side. "They can't play post-office," she said. "I'm the only girl!"

I rescued her by sending the refreshments out at once.

217217 April 20. Norman has been poring over the Farm Journal ads. The appealing post card he has written seems worthy of sharing. It is addressed to "Miller Hatchry, Bloomington, Illinois," and reads, "Dear Mother Miller: How much would you give me to chicks for? I have no money but maby you could let me have 4 or 5 and then when they lay eggs I could take them to the store and get feed, but I wouldn't need to much feed cause there just lots of little bugs they like. Goodby mother Miller, Love, Norman." I'll gladly give him our whole flock of chickens, including that bobtailed, speckled hen!

April 25. Norman got his tenderfoot badge this week. He went on an over-night hike Friday. He rode driftwood down the river, and ate pork and beans, and turkey eggs. It was stormy and cold when they left, and I worried. He came back safe and sound, and as I saw him trudging home across the square with his pack on his back, I was glad I had let him go.

I spent yesterday afternoon making a black skirt for Marilyn, out of an old dress of mine. The eighth grade glee club is performing in the concluding day of the Fine Arts week at school. She had to have a white blouse and black skirt.

Twenty years ago, I paid $18.75 for that dress. For six years it was my best dress. (I had married in the meantime.) After twenty years, my daughter wears the skirt. It has come back in style. They call it, "the new look."

April 29. I didn't know Norman had ordered a camera from Clint, Texas, until it arrived Saturday, C.O.D. for $1.98. Norman had saved his birthday dimes and nickels, changed them for a silver dollar, then lost the dollar. He earned a quarter chasing foul balls on the square, put it in his shirt pocket, and lost that too.

"Well, Bill Sanders will pay me 25T apiece for making boxes to ship poults in," he said.

So I let him go ask for a job. Bill let him help Dexter rake and burn brush. He paid him 15T and a paper sack full of turkey eggs. I bought the eggs for $1.00, but he had to pay a scout fee with that. So I offered him 25¢ an hour if he'd work in the garden. Monday afternoon I set him to planting corn. He hadn't worked long before he announced he didn't want the camera. He was going to let it go back.

"Daddy doesn't have to work near this hard for his money," he grumbled.

"Whoops," Marilyn shouted, "I'll garden for 25¢ an hour, and get the camera myself."

"Go ahead," I said.

Furious, Norman said, "Boy, if you get that camera, you'll be sorry. I'll tip your doll cupboard over."

circa 1946

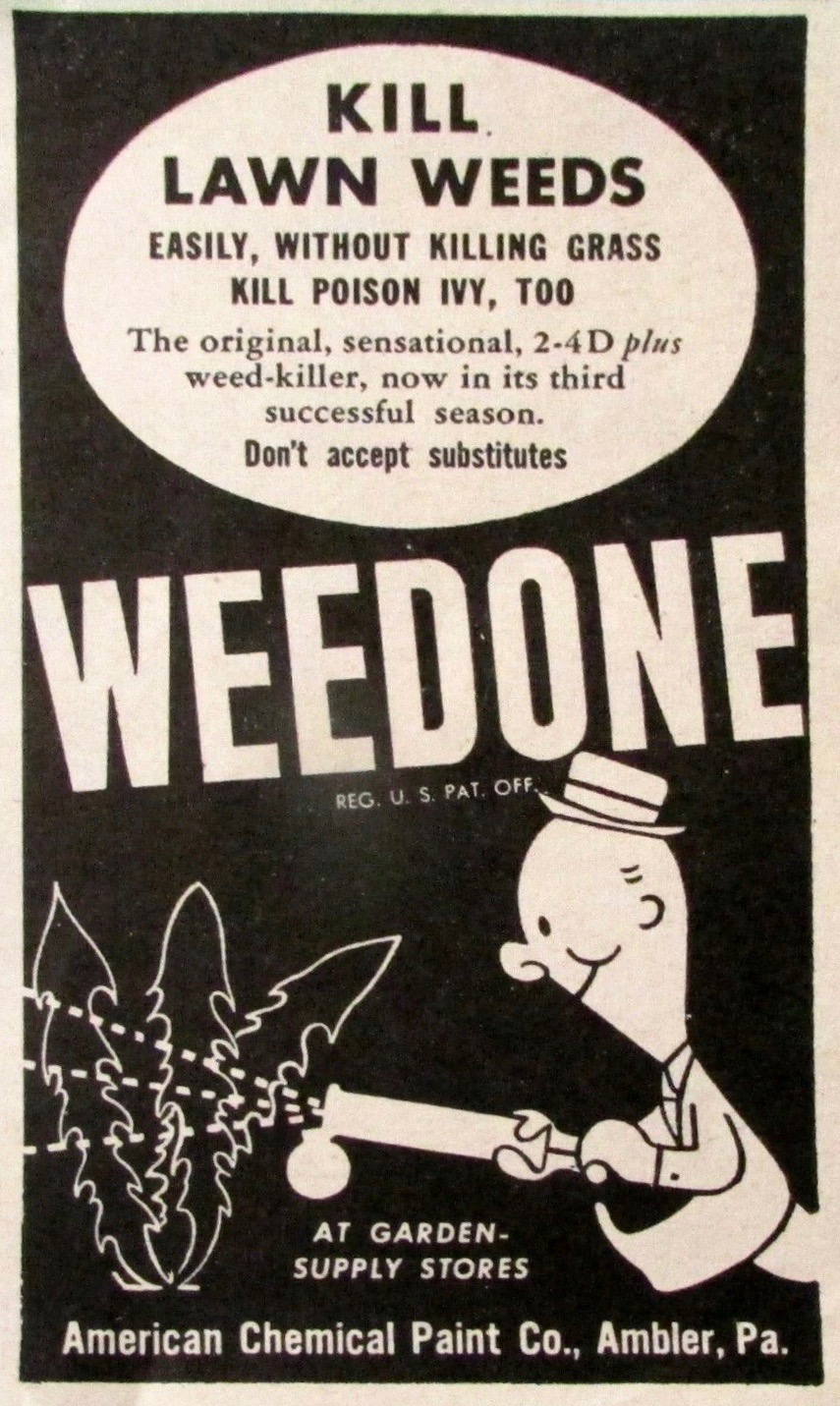

Sitting side by side on the kitchen table, their legs dangling, a verbal battle was on. They began to boast of their earning capacity. They were going to be the best strawberry and cherry pickers in town. Marilyn was going to put Weedone out for me the following night. Norman was going to pound on her if she did. She hid the spray and Weedone in the attic so he could not find it. That was Monday. This is Thursday. The Weedone is still in the attic, and Norman has worked for me one hour since then. Now he's begging for me to advance the money so he can get the camera.

218218 The living room floor needed waxing, so today I lit in I scrubbed about half the old wax off, then moved the piano. That did it. My ambition was shot. Gordon took over. Kneeling on the pillow I had on the floor, he enjoyed scrubbing up a pile of soap bubbles around him.

"Oh Gordon,' I exclaimed, " what a wonderful help you are."

He scrubbed, and I mopped. We did the other half of the floor, then scrubbed right on into the kitchen. His little arms were just a going. He sighed two or three times, and I urged him to quit.

"I'm tired," he said, "but work is too much fun to quit."

After scrubbing, he took the hoe and cleaned a strawberry row from the drive, clear down to the bottom of the lot. Not quite five is a wonderful age.

Then DeMar came home from Primary and howled when I asked him to hoe a row of strawberries. His assignment was only a third as long as the row Gordon had done. And he grumbled at it until dark, then finally did it when he realized he couldn't have supper until he did. Laziness sets in at the age of nine. Which reminds me of M. E. Minnick's little poem, "Helping Hands."

Helping Hands

They helped with the dishes and swept the floor

When they were only two and four.

They helped with everything I'd fix,

When they were only four and six.

They helped, with reminders now and then,

When they were only eight and ten.

I miss them now, those helping hands.

I'm sure each mother understands.

This tragedy I had long forseen:

You see now they are twelve and fourteen.

April 30. Today I hoed the garden until it was all clean. I couldn't find a decent shovel or hoe. The kids must have hopefully misplaced them. All I could find was a cane topping hoe with an 18 inch handle, so like a gnome, I stooped through the garden with it. Clean looked so good that I even grubbed out the hollyhocks, cosmos and asparagus. Then I stopped to pack May Day lunches for the kids. The ward was having a celebration on the square. Norman's class went on a school outing to Zion.

My baking dragged into the program hour, because I stayed in the garden too long. From the front door, I watched little girls in yellow crepe paper dresses braid the maypole.

Terry toddled in announcing, "I need a dish." So I fixed him a ham-burger in a napkin. "I don't want that. I want a dish."

He got out one of our best breakfast plates. We only have half a one around.

"Don't take that Terry. Here is a shiny molasses bucket lid." "A lid is not a dish. I want a dish."

You don't argue with Terry, because there's only his side, so to get rid of him, I trusted him with the plate, with his hamburger on it. As he stepped off the front porch he stumbled over a scooter, and away went his 219219 bun and plate. I picked both him and the broken plate up, and taped up his cut thumb. He made a terrible fuss because I wouldn't give him another plate. Finally he settled for a battered blue and white enamel one. I put my last pan of rolls into the oven, and went out to join our children. Terry was seated at Iverson's table.

"What goes on I asked.

"Terry asked if he could eat with us, and we told him he could when the spuds were done," LaFell said.

"The little tramp!" I exclaimed.

"Leave him be," cleone said.

I ran back to my oven. Then in trotted Terry with his plate full of potatoes and sausage. He came for a spoon, then back he went to join the Iversons. Sometime later, he came through the kitchen door with a contented sigh, and a fat cooky.

"Iver give me more potatoes," he said, sliding his dirty dishes into the sink.

Then Gordon came in, weary and happy. "My," he exclaimed, "that was sure lots of fun, Pansy gave me sandwiches and cake."

"Gordon," I cried, "why didn't you come in the house and get your lunch?"

"Because I wanted to see what Pansy's food tasted like," he said.

I had let Norman get his camera out of the post office so he could take pictures on his school outing today. He took sixteen shots, then broke the lens. Then he unloaded the camera while in Zion, and lost the empty spool. I looked the camera over. The shutter doesn't even open. All it is good for is to look at.

When I went to get the dirty dishes out of Norman's lunch kit, there was a bottle with a scorpion in it. He's just like his dad.

May 2. I've always wished I could be in the middle of a whirlwind to see what it was like. Today, at a most inauspicious moment, my wish was granted. We were almost to the top of the square on our way to sacrament meeting. Lolene was in my arms, and Terry and Gordon were trudging beside me, when a dirty little whirlwind caught us in its funnel. It was like being sucked up in a vacuum cleaner. I squatted down on my heels, turning the baby's face against me, while the little boys huddled close beside me. Swirling dirt stung our skin, pelting us like buckshot. We were choking for air. Then suddenly, the dust devil whirled on, spending itself in Wilson's field. Brushing off the grit, I combed our hair with my fingers, and we continued on to sacrament meeting.

May 4. Terry runs away whenever he can give me the slip. Usually he does not come home on his own, but this evening I did not go after him. The sun was down when he trudged wearily home. "I runned away for twenty hours," he sighed. He dozed off in his high chair before he'd finished eating.

He loves Lolene. "She sure is cute, ain't she," he says.

May 6. I lost Terry again today. I searched the yard, and called, then gathered up the other kids and told them where to go looking for him. We were arouped by the little bridge at the front gate.

220220 "Terry," I shouted once more.

"What?" Terry answered, his voice echoing from Under the bridge, where he contentedly lay in the cool, damp sand.

The kids whooped with laughter.

"Terry was laying down," he said with wide eyed innocence.

May 9. Mother's Day. DeMar presented me with a paper bag of woody carrots that have been in the garden for over a year. Written on the sack was , "To Mother from DeMar and Gordon." Their radiant smiles, as I peeked into the sack, warmed my heart.

"Now we can have carrot pudding for dinner, can't we DeMar beamed.

"If you'll grate the carrots," I answered.

So he did.

I waited all evening for Winferd to come home. He said he would, but he didn't make it.

May 14. Winferd came last Monday. He brought me a pink linen suit—the nicest one I have ever had. It is so extravagant. And he needs a dress suit. He hasn't had a new one in twelve years. He doesn't even own a pair of overalls that hasn't been patched time and time again. And now he's gone again. He left for Iron Springs today noon. He hopes he'll be home Sunday night. So do we.

Terry ran down the road screaming after the car when he left. I caught him, and held him tight in my arms, but he squirmed and cried all the harder, asking over and over, "Why didn't you let me go with Daddy?"

The hour grows late, and the house is quiet. The kids have been celebrating the closing of school. Marilyn and Norman and their friends have been making candy and playing the phonograph. The living room is a clutter of bingo cards and phonograph records.

I've just made the rounds, and everyone is asleep. You'd never guess to look at them, that Terry and Gordon had been sent to bed early because they went swimming in the ditch with their clothes on.

June 3. With eternities before us, why are we so rushed? Take the strawberries, for instance. They are only on the vines two or three weeks a year. So we drop everything and pick berries and put them up. Then comes the cherries , and so on, the calendar around.

Winferd got through tromping wool and came home, but we hardly see each other. He went right into the haying and planting cane, and now he's helping his dad and Van drive the cattle onto the summer range. They've spent all week trailing to the mountain and back.

Grandpa took Marilyn, Shirley and Terry to Mt. Dell with him Tuesday. When he brought them home, Terry ran in front of the car and was knocked down. A wheel ran over one knee. Now it's blue and swollen.

Terry has been a tyrant about running in front of cars. The kids report that he stopped four cars Sunday afternoon. Grandpa may have saved his life by hitting him. It may make him more cautious.

Wednesday was a red letter day for Marilyn. She went to Primary as a teacher. This is her first real office in the church. She is an assistant to Norma Sanders in the smallest age group.

221221 When Marilyn got ready to go to Primary, Shirley asked, "What's Marilyn going to Primary for?"

In a taken-for-granted-tone, Marilyn replied, "I teach."

Then DeMar came in. "What's Marilyn going to Primary for?" he asked.

Nonchalantly, Marilyn answered, "I teach Primary."

The same thing happened when Norman entered. What an important milestone!

Lolene has two little bottom teeth that show each time she smiles.

They are very exciting teeth. All six of her brothers and sisters have to inspect them, and she laughs at their attention.

It's fantastic how much Norman can get out of a nickel when he spends it on penny post cards , and in his own seclusion, answers ads. Today, a freight truck pulled into our yard.

"Does Norman Gubler live here?" the driver asked.

"Yes he does," I replied.

"Then this freight belongs to him." Grinning, he pulled out a pint-sized package, postpaid from "Old Peachtree Lane, Ind." It had cost the company 60¢ to send it to Cedar. I had to sign papers and dig up another quarter.

The truck driver mused, "They could have mailed the package clear across the United States for a dime."

But the package contained a can of plastic wood and one of solvent. The solvent is flammable.

"Oh boy," Norman said, "now I can make models and sell them. I'm going to start a new business."

He has made a bailing wire form and molded an ostrich onto it.

We've been hounded with dunners from a stamp collecting outfit, for $3.00 to pay for stamps Norman ordered with a penny post card. The stamps, fortunately, never arrived, so I have requested that the dunners stop.

The other day, Norman got a packet of literature on how to remodel his old home into a "dream house." Marilyn and Betty Segler had so much fun over this, that Norman refused to even look at it. Now he's dreaming over a premium catalog, contemplating the treasures that will be his, when he sends another penny post card for seeds to sell.

June 5. I mixed food coloring into three pounds of margarine this morning. We've been eating it white for almost a year, because it's too messy to color. (Note: Colored margarine had never appeared on the market up to this time, because of restrictions placed upon it by the Dairy Association.) Shirley has been eating her bread dry, refusing to use a white spread. She padded across the porch in her bare feet, and sat down by me on the step where I was finishing working the color in. Her voice was soft and happy as she said, "I like butter and bread." She ate it each meal today and in between, it has tasted so good to her.

At dinner, all of the kids spread their bread with new interest.

"The only difference between this and margarine is the color," Norman said.

222222 "Oh my! There's as much difference as day and night," Marilyn said. "You could never fool me. This butter is nothing like margarine."

Winferd winked at me. Funny, but it tastes different to me too. It is much better. Really, we eat with our eyes.

June 23. Shirley has cried over everything lately. Sometimes I'm beside myself. This morning, she came wailing into the laundry room.

"Shirley," I said, "what would you rather do in the whole world?"

She stopped crying and thought a minute. "I don't know," she said.

"Well, what would you rather do, have a new toy, go to a picture show, go on a picnic, or what?"

"Go on a picnic and eat pork and beans," she said.

"Ok. We'll go on a picnic and eat pork and beans, and have cake too, if you'll not cry for a whole week. Do you think you can go that long without crying?"

Ducking her head, she said with a half grin, "I don't know."

"Well, you'll try, won't you?"

"Yes," she said weakly.

She has taken the teasing of her brothers all the rest of this day without tears.

June 24. Norman gave Shirley a trouncing today, but she didn't cry.

June 30. Shirley's week is up today, and she still hasn't cried, so we're going to Oak Grove.

July 2. Shirley cried twice while we were at Oak Grove. I guess she really needed to. But she told Gordon she couldn't cry at home any more, because we were going on another picnic.

Norman brought a baby pack rat home, planning to raise it on the bottle. The little thing died.

July 21. Sarilla Hepworth had asked us to get a program number for the morning. of the 24th.

"How nice," I said to our children. "Marilyn can play the piano, and the rest of you can dramatize the pioneer song, 'No Sir No.'"

For two weeks I struggled with my troops, trying to teach them the song, but they only hung their heads as if afraid. Yesterday, while Marilyn was horseback riding with Ramona Firm, I decided we'd practice without the piano. But I could scarcely get a peep our of the kids. I coaxed and I pleaded, then finally DeMar inhaled, and swelling up like a frog, he blasted, "Tell me one thing, tell me truly, tell me why you scorn me so, etc." I nearly toppled over.

Catching the spirit, Shirley shouted, "No sir, no sir, no sir NO!"

And Norman boomed, "My father was a Spanish merchant, and before he went to sea,"

"Hey kids, not quite so loud," I motioned with my palms.

"First you want us to sing louder, and then you don't," DeMar grumbled.

223223 "Ok, belt her out," I said.

And they did, each in a different time, like singing a round.

Tonight, I lined them up to practice the action. They were tired and touchy. Shirley's chin brushed DeMar's shoulder, so he punched her. Her eyes rolled back in mock agony as she doubled up howling onto a chair. So Norman flipped DeMar on the cheek, and he howled. In despair, I marched them off to bed.

July 23. I seemed to have two choices, both of them bad. We could either practice without the piano, while Marilyn was off horseback riding, or practice before her company, which she always had. I chose the latter. So Ramona sat in a corner while we rehearsed. When Marilyn started to play, Shirley ducked her head, so DeMar punched her and she bawled.

"Oh no," he moaned, flopping onto the couch.

Disgusted, Norman pounced on DeMar.

"Ow, ow, ow, you broke both my legs," DeMar howled, going down to his knees on the floor.

With my one free hand, I grabbed Norman by the collar. The baby was perched on my hip, and my other arm was around her. I needed a miracle.

"Ok you guys, it's time for everyone to kiss and make up." Letting go of Norman's collar, I kissed his forehead. He would rather have been clobbered.

"I don't want to kiss old DeMar," he muttered.

DeMar shuddered and looked at Shirley. Ramona sat silently in her corner.

"Here," I said, putting the baby in her lap. Picking up a pencil and paper, I said, "You can each speak just once while we practice. If you speak the second time, you don't get a show ticket tomorrow, so choose your words well."

Marilyn played the piano, and the others marched in with a little waltz step, pretending they were on stage.

"Mother, why don't we do it this way?" Norman asked, demonstrating.

"You've spoken once, Norman."

They danced into place and sang, racing ahead of the piano.

"They don't even try," Marilyn lamented.

"You've spoken once, Marilyn."

They sang some more. They lagged in places, and Marilyn pounded the piano harder.

"Softer, Marilyn," I pleaded.

She bit her lips and glared at the piano. The kids performed like puppets, afraid to speak. They were never with the music. I could see pressure building up. I was afraid Marilyn would explode, so we made the rehearsal short.

July 24. Eldon and Edward slept with Norman and DeMar last night. They played until midnight. Marilyn and Ramona tended Elco Orton's kids and didn't get home until 3:00 a.m.

224224 Getting the kids to the church house by 9:00 a.m. was a squeeze. I hurried behind the scenes and pinned on their costumes. They were dressed like a boy on one side and a girl on the other. Norman and Debar wore Marilyn's outgrown dresses. I had just put in the last pin, and started to make Norman one rosy cheek, when their number was announced. We squeezed behind the extra wings and stage props, but I couldn't hear any piano. Panic seized me. We had left Marilyn at home taking bobby pins out of her hair. I visualized her still there in front of the mirror. Then the piano started to play. But I was stuck in the wings. There was only a six inch space back there. The kids made it, but I was just half way through, and couldn't go either way. I had to push the scenery out where the people could see, before I could get free.

The kids were singing, so no one paid attention to me. They turned the boy side to the audience when the boy spoke, and the girl side when she answered. Fortunately, they found someone in the audience to grin at, so they sang out. My agony was vindicated by the hearty applause.

July 25. Since I've been in the Relief Society presidency with Belva Sanders and Ruth Nielson, I have to go to the early morning welfare meetings, an hour before Winferd's and Norman's priesthood meeting. This morning, when I called goodbye to the family, Gordon wrapped his arms around my legs so I couldn't walk.

"I wisht you had a awful bad cold so you couldn't ever go," he said affectionately.

July 26. Winferd picked over a case of Himalaya berries this morning. "Make a whole row of pies," he said, "so I can eat 'em careless like."

I made five juicy berry pies for him.

Norman and DeMar were supposed to pick berries too. At sundown tonight, we took Terry and Lolene in the cart, and Winferd and I walked up to see how they were getting along. They were getting along fine, playing on Horatio's lawn. (Horatio lived by the briar patch at that time.) When the boys saw us coming, they dove behind the bramble, and began to pick. By the time it was too dark to see, they came home with three cups of berries. Sweat had trickled through the grime on their faces, and their mouths were purple. The only thing that was clean was the whites of their eyes.

"You guys wash up for supper," I said.

Norman darted into the bathroom, turned on the faucet , and darted out again, looking like a racoon. He had rubbed a hole in the dirt around his eyes and mouth.

"Get right back and wash," I demanded.

In half a minute he was back, more racoonish than ever, with the holes a little whiter. I marched him back to the bathroom, and with a clean washcloth, I scrubbed.

"Seems like I was four years old again," he giggled. "I remember how I stood on a stool while you washed me."

He was clean when I got through, but complained that the back of his ears felt cold.

July 30. Winferd sold some grain for cash today, so now we can go to the Stake Relief Society bazaar in Springdale tonight. I never found time to make a sewed article for it, so I potted a sword fern to take, and asked DeMar to shell me a quart of walnuts, and Norman to pick berries. When DeMar 225225 finished his nuts, he was so pleased, because it took him less than two hours when he had been so sure it would take him a week. Winferd and Norman picked four baskets of berries during the noon hour. When Hilda Bringhurst, the Stake Relief Society President, called for my collection, she thought it was a wonderful one. I felt so good about her feeling so good that I realized I'd never get any reward in Heaven, because I always get it here.

August 1. At the bazaar I bought a dress for Lolene, a blouse for Marilyn, and an apron for me. Winferd bought cookies for the kids, dried peaches for DeMar, and some good homemade noodles. He was just a little burned up when he saw the berries that he had picked from the briar patch, go for 12½¢ a basket. They sell in the store for 35¢. I cheered him by reminding him of how good the guy felt who bought them. Like I did about the blouse. It had lots of trimming on it, and was the very latest for style. I suspect some woman resolved to never sew again for a bazaar. Bazaars are nothing but make-work projects for women, whose efforts are sold for a pittance. Bizarre!

August 9. I'll have to get Winferd some iron shoes to hold him down. He's been counting his gold for the last five days. The pear market is up—$5.00 a bushel, compared to 40¢ last year. Last year they went as culls. This year they are perfect. Winferd is dreaming of a new car. All I ask is to be out of debt and to see our store house filled.

We got a package from Popcicle Pete today. I had written a letter of exasperation, attached to a package of dirty popcicle bags. I told Pete I was sick of the litter, because my four kids scrounged every filthy popsicle bag they could find from under the grandstand, and out of the weeds along the fences, and were saving them up to get prizes. So I was stomping the mess down inside a big paper sack, 153 of them. We received an entertaining letter from Pete, saying he was sending prizes to all four kids. He sent four yo-yo tops, four singing lariats, four note books, four magnifying glasses, four whistles , and a bundle of crayons. The singing lariats were the most fun of all.

Winferd has seven Navajos camping in the pear orchard. Their little girl, Evelyn, came to the house, and I had her try Marilyn's red coat on. It was just fresh back from the cleaners.

"Oh dear, it's too big for you," I said. Her face fell. "Do you want to keep it until it fits you?" I asked.

Timidly she smiled, "Yes."

She came with her mother to a ward program tonight. Hot as it was, she had the red coat wrapped lovingly around her. It matched the velvet her mother wore.

August 11. I went to the orchard to show the Indian women how to dry pears. They were pleased, putting out a real lot of them in one day. They will enjoy them next winter.

Winferd swapped help with my brothers, Bill, Clint and Wayne. They did some tractor work for Winferd, and he is hauling wheat for them from up above Zion. The wheat, hay, and pears are all ready to harvest at the same time.

I was busy washing when a shadow darkened the door of the little house where I worked. There stood Winferd in his patched, faded overalls. His face was rough, because he shaves only on Saturday, unless we're 226226 going somewhere important. He looked kindly at me.

"Forget the washing, and go pack a lunch. The family might as well go with me to Zion. You and the baby can ride in front with me, and the kids can ride on the grain sacks."

The lunch was simple and quick. As we rode, the baby turned round and round on my lap, like a top, or climbed up into my hair. The only time she fussed was when I wouldn't let her eat the stuffing out of the ragged truck seat. The kids hooted and yelled all the way through the tunnel, and Winferd stopped long enough for them to feed some bread to the squirrels.

Bill and Clint were riding the combine when we reached the ranch. Wayne was at the gate. The other guys said he was just a tourist, but Wayne reminded them of all the good he did. The wind blew the chaff back from the combine all over my brothers and I wondered how they could breathe. We jogged in the truck across the furrows to the one shady spot on the further side, to eat our lunch. The wind blew little specks all over our beans so they looked peppered. But they tasted good. Lolene choked on a pine cone. What a pest she was. I had to eat standing up, so I could keep her in the boys' pickup. When Winferd was loaded, we returned home. DeMar stayed to come home with my brothers. He brought a baby jackrabbit home with him, but the wise little thing ran away.

August 13. Last night the Indian man, Dan Taylor, came to the house. "When we pick across the street (Ed Gubler's orchard) my wife, she fall out of tree. She sick. You got medicine? She hurt."

I gave him six aspirin. I was afraid to give him more, for fear she'd take them all. "I'll come right over," I said. I was worried.

When I got to their tent, Dan's wife, Nary, was in bed. She was in real pain. I tried to get the doctor, but he was in St. George. Winferd and the boys were on the mountain, so I got Jack Eves to take Dan and Mary to the hot springs. When Winferd got back at 10 p.m. we went down in the canyon to get the Indians. Mary cried with every step she took to the car.

This morning, as I talked to the doctor, I told him how it hurt mary to walk.

"If an Indian woman can walk, she'll get better." He wasn't anxious to see her. "If she doesn't get along, bring her over, but I think she's just badly bruised. The hot springs will help her." I took some apple and blackberry jam over to cheer her, and to see how she was. She was sitting on a canvas cot under a pear tree. Her knee was hurting, and her head ached. She wanted more aspirins.

"Is there anything else?" I asked.

"Cookies," she answered.

What a relief! I knew then that she was aoing to get better. I sent her the cookies , and Winferd took her to the springs again tonight. He said she could walk much better.

August 14. Evelyn slept at our house last night. She asked to sleep between white sheets. I fixed a bed on the couch, in front of the open windows. She kicked off her shoes, and piled in with all of her clothes on. This morning she enjoyed washing up in the bathroom, and combing her hair in front of the hall mirror. She ate breakfast with us, and stayed until her mother sent for her.

227227 August 20. Clark took the Gubler grandsons fishing on Ashcreek. Norman caught fifteen suckers.

Dan and Mary Taylor came for their pay last night, and to see what size of rug I would like. I felt humble in front of them. Making a rug is so much work.

"Only take three, maybe four days," Dan assured me. 'Ile grow own wool and make own yarn and dye too."

"We make it 2½ feet by 4 feet to go here," Mary said, indicating the couch.

Those people are so poor, I found myself fighting to be able to accept a gift from them. But they wanted to give.

"Ok," I said, "send your little girl over, and let me take measurements so I can make her some school dresses."

This pleased them very much.

August 24. While I was in the bathroom giving our slimy little water turtle, Herby, a bath, there came a knocking at our kitchen door. With Herby in his tray, I went to answer.

"Edith!" I exclaimed.

"Ugh!" she greeted, looking at the turtle. I was so glad to see her that I almost forgot how we both hate to be kissed, but she didn't let me get away with it. Her right arm stiffened, and she shook the hand that was dripping with Herby's bath water.

Edith's girls are going to sleep here, and she and Gene will stay with Mom. The Gubler men folks are fishing above Zion.

August 28. Our house has been as noisy as a flock of blackbirds. To have new girls in town as pretty as Edith's girls , has been the magnet to draw the neighborhood kids. DeLoy Wittwer is staying with us too. He has taken a shine to Corinne.

Winferd took the girls to Rattlesnake with him after a load of farm machinery for Bill. The baby and I went for a visit at Mom's. Annie and Rass, Mildred and Maurice, Kate and LaPriel and their families were there too. All six of Mom's girls were home for the first time in years.

September 9. This is the busiest season of the year. So is spring, with its planting and digging. And summer, with its weeding and watering. And autumn, with its canning and harvesting, and the opening of MIA, Primary, and Relief Society. And winter, with ward functions and socials , and the crowded days of mending and sewing. NOW is always the busiest. Especially this NOW. We've put up peaches, pears, figs, grapes, beans, tomatoes, spinach and corn. There is no end to what our fruit shelves will hold. Winferd keeps coming in, five gallon buckets weighing down each arm, and an aren't-you-glad-I-brought-you-some-fruit expression. I sigh, try to be grateful, and struggle on. Like the ant, I know we have to eat next winter, but oh sorrow! I am a grasshopper at heart.

We sold our sway-backed, sad eyed old cow to Wesley Hafen today for $125.00. Already standing in her place is a young heifer Winferd bought from Alma Flannigan for $125.00. Just like trading.

228228 I named the new cow Elsie because she has the cutest face I've ever seen on a cow. It's easy to imagine her with a bow of ribbon on her head, and a garland of flowers around her neck. Her eyes are big and brown, and she has long, curly eyelashes. She's a very dark red, with black smudges around her nose and eyes that give her a saucy expression. This was love at first sight.

September 10. This morning, Alma Flannigan knocked on our door. "Good morning," he said, "I had trouble sleeping last night. That's why I'm here so early. Winferd, I got the best of you on the cow deal. She's only a range cow. She'll never make a good milk cow. She's not worth more than a hundred dollars."

"You didn't set the price," Winferd said. "I offered you $125.00."

"Please come out to the pickup with me," Alma urged.

Winferd went out. Alma opened up some cases of new molasses buckets. "There are $25.00 worth here. Will you please take them so my conscience can rest easy? I want to be able to sleep tonight."

"I need the molasses buckets," Winferd said, "but I prefer to buy, them from you."

"Please accept them," Alma urged. "My peace of mind is worth much more than the money."

No amount of money could have ever impressed us as much as his example of honesty.

Winferd had to deliver pears to an outfit in St. George today, so he took the family along. He took us to the College Cove for milk shakes. When he sat down with the baby in his arms, I took her from him.

"I'm used to eating with her on my lap," I explained.

Winferd put a nickel in the little slot at the table to show the kids how the juke box worked. It obliged with "Carolina Moon." The waitress brought the big glasses of ice cream with straws in them. Lolene stood up on my lap and grabbed. She put her little mouth over my glass, so I let her drink. She wouldn't let go. When they brought the ice water, she climbed across me and tipped Gordon's cup over. The cold water startled her, and she cried. I grabbed all the paper napkins available and began mopping up. Lolene wiggled loose, and pulled my milk shake over on us.

"You said you could handle her easier than I," Winferd chuckled.

September 13. Winferd bought the nicest spatted cow and calf from Elmer Hardy, both for $200, and this one produces. We live again!

September 23. I churned Monday—the first real butter for over a year. Since Shirley is the one who felt bad about eating margarine, it was appropriate to churn on her birthday. We've been having cream on our cereal, and cream on our fruit, and milk for dinner, instead of water. Winferd thinks two cows are a nuisance, but it worth it.

Winferd made arrangements to take the truck to Fredonia for Maurice Judd to overhaul. Whenever the truck moves out of the lot without Terry, he goes yelping down the road until Winferd stops and picks him up.

"Winferd," I said softly, "would you like to take Terry with you?"

"Do you mean take him to Fredonia?"

229229 "Don't be alarmed. It was only a suggestion," I said.

"He'd only get in the way. He'd get all covered with tar and grease from hanging around where I'll be working."

"Don't worry about it. He can stay and play with Lolene. We like his company," I said.

Winferd kissed me goodbye. When he went out the back door, Terry was patiently sitting in the truck. With round-eyed anticipation, he peered above the door.

"Terry, come here," I called.

"I want to go with Daddy," he said.

"Daddy is going too far. Daddy is going a long way off."

"I'm going a long way off with Daddy too," he said firmly.

Winferd looked helpless. "You'd better get him ready, I guess."

"Come on then Terry, and get clean."

He looked so cute and sweet when I kissed him goodbye. I hope Winferd won't be sorry he took him. And I hope they hurry home to take over the milking. The Hardy cow, Old Maude, is hard to milk. She gives a lot, but it's like filling a bucket with a medicine dropper. I get paralyzed sitting so long. Elsie only gives a couple of quarts, but she gives it easy. She's a pet. She loves to eat apples from my hand and to nuzzle up to me.

I've been released as Stake Special Interest Supervisor, and sustained as manual counselor in the Stake YWMIA,.to Margaret Nuttal. Bessie Judd is the activity counselor. We're attending conferences in all of the wards. Back in my Stake Sunday School days, I once thought I'd never get called on to talk. I was surprised out of this smug complacency enough that I learned to never go without some gem of thought. It's a good thing I did. I've been called on five times in the last two weeks. I'm like a little minnow bobbing up in a whirlpool. I think I've had my cycle. Winferd, Marilyn and I were all on the program Tuesday. He conducted the recreation hour, Marilyn played the preliminary music, and I gave the lesson to the Special Interest group.

This morning I typed seventy notices about our cleanup campaign, while my floors went unswept, and the breakfast dishes dried up in the sink.

September 24. Norman has a talent for getting knocked out when he's needed most. He got in a fight over a spit wad Tuesday, and feels miserable/ looking through a purple, swollen eye. And then yesterday, a wasp got him_ when he knocked its nest down. His right hand is swollen shiny tight. He can't shut it to milk.

I got Marilyn to milk the little cow. It is her first time. She put on her newest blouse and best skirt, and carefully put on her lipstick before coming to the corral. I sent her back to the house to get into something more practical. When she finally came back, she hedged around and around the cow, trying to decide where to light and begin.

Finally, she asked, "What is the cow waiting for?"

"The cow isn't waiting. That's you. Sit down and go ahead."

She brought the milk in just before bus time, but I had to give it to the chickens, it was so trashy.

230230 September 29. When Winferd and I came home from our shopping, Norman greeted us with a blast from a second-hand trumpet.

"Where did you get that?" Winferd asked.

"From Kent Wilson. He wants $25.00 for it. Mrs. Clifton says it is worth $60.00."

"Then I guess we should be willing to pay that much," Winferd said.

"Mrs. Clifton said my mouth is the right shape for a trumpet."

It must be. That trumpet has been blasting all evening.

October 21. The hunting season is on. Winferd is on the mountain with his dad, helping with the roundup. Of course, his gun is on his saddle.

October 31. The shadow of sorrow descended upon our home yesterday. The day dawned dark and dripping. Winferd did the milking, and chopped a pile of wood.

"If this storm breaks, we'll have freezing weather," he said. "I'd better pick the beans."

Working fast in the chilly mist, he filled a bushel basket, then doubled up in pain before he could get to the house. I sent for Ovando, who took him to the doctor. At eleven last night, Dr. McIntire and Ovando returned from the Iron County Hospital, where Winferd went into surgery. He was operated on for appendicitis, but that was not the problem. What is wrong, I do not know.

November 1. Neighbors and family are good. Ruth and Bill took me to Cedar to see Winferd yesterday. Morris Wilson called to see what farm work was most pressing, so the High Priest's Quorum could help. Aunt Mae Gubler came to let me know she would stay with the family whenever I needed to go to the hospital. Gretchen Stratton sent the same message. Vernon and Greta Church took me to see Winferd today. Winferd was in an oxygen tent, but he smiled at us. Uncle Will Palmer came and helped Brother Church administer to him, then they left us alone with each other.

Sister Church said, "We'll wait downstairs. You stay as long as you can."

I could see Winferd through the windows of the tent. He studied me too much. What was he thinking? Fear gripped me.

"Dear Heavenly Father," I silently prayed, "please forgive me for being so weak."

Trying to gain the strength I needed, in my mind I repeated over and over, "Trust in the Lord with all thy heart, and lean not unto thine own understanding. In all thy ways acknowledge him, and he shall direct thy paths." The clouds of doubt began to dispel, but still I was sad.

Churches were waiting, when I came down stairs. Oh, my very dear neighbors. How much I loved them.

Bishop Church said, "What would you like to do now Shall we go to a show?"

"This is your night out," Sister Church smiled.

"I hope the kids will be all right," I said.

231231 "We had better just go out for ice cream, then take you home so you won't worry," Brother Church said.

November 3. Winferd is getting well. He will come home. I went with his dad and mother to see him last night, and he even laughed and joked with us.

I had been to the polls, with a note signed by Winferd, asking permission for me to vote for him. The judges couldn't accept it. Max Woodbury was there, coaxing them to let him cast Ellen's ballot, but they turned him down too.

Calling Max aside, I asked, "How would Ellen have voted?"

"For Truman," he answered.

"Good. Winferd would have voted for Dewey. That makes it just as good as if both of them had voted."

Winferd chuckled when I told him. He was also pleased that the judges of election had snapped the bushel of beans that he picked, so I could bottle them. Belva Sanders, Myrtle Segler and Sarilla Hepworth were the judges. Cleone Iverson stayed after she voted, and helped too.

I have been memorizing a part in the Stake MIA play. Rhea Wakling, the Stake Drama Director, relieved me of the part.

"I'll do it myself," she said, "and you can tell the cow goodbye."

She thought it funny that I had memorized my part by laying the play book on a newspaper under the cow while I milked. Really, it was my best study time. My face burned a little when Ferra Lemmon walked up to the corral gate once, and caught me reciting to the cow.

November 4. Our first wintery blast. The north wind shook all the windows and sent it's icy fingers in through every crack. Even the inside of the house had a frosty breath. All that is left of the coal pile is pulverized powder, and our wood isn't sawed. The weather has been fair, and the wood Winferd chopped has held out until last night. I kept just enough to start the furnace this morning. I kept the baby in bed as late as I could, because we had no heat. When I looked out, I saw that Elsie had crawled through the corral fence, and was under the pearmain tree gorging herself on apples. After I lit the furnace with our last piece of wood, then covered it with smudgy coal dust, I put breakfast on, and routed the kids off to school.

Lolene followed me back and forth in her walker. "Terry, take care of little sister while I milk," I said.

Taking a bucket of dairy mash, I tried to coax Elsie out from under the apple tree. Disdainfully she sniffed at the bucket and began picking more apples. Slipping my hand through her halter, I gently led her toward the corral. At the gate, she shook her head, which plainly meant, "No." We were deadlocked. I pulled and she pulled, and neither of us budged. She barely had her nose in the gate, and I realized she was the biggest. Helplessly, I prayed, "Heavenly Father push her in." There was no one else to call upon.

Well, he didn't push her in, but he helped me use my brains. On the ground close by, lay three feet of rope. Still hanging to the halter, I picked it up and knotted it through the ring at the cow's chin, tying the other end through a knothole inside the corral fence. Then I got behind, 232232 gave Elsie a boot with my foot, and she went in

When I went to the house for hammer and nails to fix the fence, Grandpa Gubler was in the kitchen talking to Terry.

"Should I get Clinton or Walter Segler to come saw the wood?" I asked.

Grandpa looked surprised. "I thought the oil you got Saturday night was for your furnace."

"No, that was for the water heater.'

"My goodness," he said, and went out and picked up our dull old axe.

I rummaged through Winferd's lumber scraps for a board to fix the fence. The ragged overalls of Winferd's that I was wearing were drafty. The seat and knees were gone. Grandpa dropped the axe and followed the board I was dragging.

"Let me fix that fence," he said.

"I can do it."

I trotted around the haystack with my board, but Grandpa picked up my hammer and took the board. I let him. Men have their superior moments. I washed Old Maude off and sat down to milk, and Grandpa fixed the fence and cut a pile of wood. I was on top of the haystack throwing down feed, when he backed out with his car.

"They've got too much hay down there now," he called. "They waste it when you feed too much."

I hesitated a little with the fork, but he was still watching, so I sat on top of the stack, and slid down into the manger. Sliding down the haystack is the part of doing chores that I like.

Norman phoned Max Jepson, and he delivered a load of good, clean coal. Let the wind blow!

November 5. Hallelujah! I've just this minute bottled the last quart of anything I've got to bottle. Tomatoes were the final roundup. I've counted the bottles that are filled—1,039 quarts of fruits, vegetables and meats. That's stock on hand—not counting the dozens we've used. There isn't a teaspoon full from last year. This is all fresh. It's over, and I'm glad.

December 7. Winferd came home on the 20th of November. We've petted and pampered him and half drove him crazy. He's glad to be back, but he's a peevish old bear. I thought I was being a perfect angel by ministering to him, but he brought me up standing when he said, "You don't seem to think I can do a thing for myself." It all brings home the point that nobody can stand too much sweet.

We're indebted to all of our neighbors, and all of our folks. My sisters and brothers, Winferd's folks, friends and neighbors have tended our kids, given me taxi service to the hospital, did the chores, brought beef roasts, whole turkeys , and endless good things. How greatly we have been blessed by these dear, gentle people!

December 14. Bless my soul, we're still stuffing things in bottles. Winferd has been peeling squash, and we've put up 20 auarts today. The crooknecks are fine grained and sugar sweet, and we've had plenty to share with our neighbors.

233233 December 17. This is our eighteenth wedding anniversary, and Winferd runs a constant temperature of 102 degrees. Still, he insists we're going to celebrate with Ruby and Roland tonight.

December 18. The Webbs took us to Dick's Cafe in St. George last night. I was thrilled to have a dinner date with my husband once more. While waiting for our order, Winferd reached under the table and held my hand. A strange sadness overshadowed me—an impression that this would be our last anniversary together. There was an ethereal tenderness in Winferd's handclasp—something delicate—not of this earth. My heart almost broke. But I struggled to brush the feeling away. I squeezed his hand and returned his smile. After dinner, we went to a crazy King Kong movie.

December 26. I had given up all thoughts of Christmas shopping this year, but on the afternoon of the 24th, Winferd dressed up in his brown suit and put on his best hat.

"We're going to have Christmas," he announced.

I was afraid his strength wouldn't hold out, but happy that he wanted to go shopping. We started with shirts, sox and overalls, and added a few toys. We got a fountain pen for Norman, and for Norman and DeMar together, an erector set with an electric motor that had been reduced. LaVerkin Feed had a good buy on a little red wagon, just right for Gordon and Terry. All Shirley wanted was a Kewpie doll and roller skates, and we found them both on a bargain counter in St. George, also a stuffed dog for Lolene. Marilyn needed a jacket, and we found a nice red suede one, and a patent leather purse to go with it. Last summer I had picked up a moonglow necklace and bracelet. I was glad I had them now to wrap up for Marilyn.

When we got home Christmas eve, the kids had the house shining and the tree trimmed, and the neighbors had played Santa Clause From all directions came lovely things, like fresh eggs , mince pies , raisins , ground beef and sausage, nuts, sweaters and skirts for the girls, bath towels, an electric heating pad, cards with money in, and Grandpa Gubler had brought a Check for Winferd's year's work. It was enough to pay all of our debts and to tide us over until Winferd is well again. A Merry Christmas.