EDITOR'S NOTE: "Don't Feel Sorry for Me" was originally published in The Relief Society Magazine July, 1965, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 517-520, 1965.

Brigham Young University's Harold B. Lee Library has made digital scans of Relief Society Magazine available online as part of the Relief Society Magazine Digital Project. This article is online there in the original format at:

The article is reprinted here with permission.

On my last pilgrimage downtown I met an old office friend. We stopped at a busy intersection to chat. The city streets were harassed with the snarl of the early morning traffic. People were rushing to work. Jubilantly I said, "Jake, we're moving away. I am on my last errand downtown. We're going to become ranchers."

"Ranchers!" he exclaimed. "I can't think of anything more miserable. Are you sure you know what you're doing?"

"Quite sure." I grinned.

As we talked, a little breeze scuttled between the canyon walls of the buildings stirring up cigarette wrappers and gum papers in the gutter.

"I couldn't stand to live in the country. It would drive me crazy," he said. "Are you sure you want to leave all this? Just listen!"

I listened. All of the sights and sounds around me were the gears and cogs of the big machine that was the city. The day was well in motion.

"I love it," he continued. "I wouldn't leave this, nor my office for all of your open country."

And I don't believe he would. He sort of looked like a piece of office equipment; a little too pale and already becoming hollow chested from leaning over a desk too many years.

Sadly he shook his head. "I feel sorry for you. You're making a wild choice, but I wish you luck." He gave me a goodbye handshake and I watched him sprint across the street before the light changed. He would take the elevator up to the fifth floor of an old smoky building, put his key in the door and let himself into his stuffy, paper cluttered little office. From his window he would look down on the top of department stores and service stations. In the distance he would be able to see black clouds rolling forth from a pair of smokestacks.

Back at the house I closed the drapes for the last time on the one picture window. It had been a chummy window. Always I could look out of it right into the picture window of the house next door. Our house had been cozy, but now the rooms were bare. We made our final inspection then locked the door. After we pulled the trailer out of the drive, we looked back at the yards. The grass and the concrete were continuous with the grass and concrete of the man's next door. We drove past the houses on our avenue. Each one was its own little foreign country where strangers dwelt.

I SHALL never forget the day we pulled up to the ranch house. It was early evening. The sun was settling into the grove of trees behind the barn, sending red shafts of light through the pillars that were the lodgepole pines. I stood transfixed on the wide back porch. The yard was a riot of flowers—pink peonies, painted daisies, blue delphiniums, and a carpet of purple and yellow violas that ran helter-skelter into the tall grass. From the pole fence at the edge of the garden the meadow sloped down to a meandering creek. The creek was flanked with willows and serviceberry bushes. Beyond lay the wheat fields and alfalfa bordered with quaking aspens and ponderosa pines. Dew was already gathering on the grass and the air was crisp and cool. It was hard to believe that this was home, really and truly home. It seemed more like an exotic vacation spot where one would be privileged to spend only a night or two.

A swing in the yard invited me. As it fanned me high above the corral fence I could see a neighbor's house half obscured by trees. In a sweep the view encompassed timber land and mountains in the distance against the sky. Swings are great. They aren't just for the young, but mighty fine for anyone's anatomy.

We found strawberries ripening in the garden. Daily, we heaped them high in a large glass bowl on our table. No dividing them in individual dishes from little baskets from the store. They stayed in season until the raspberries began begging to be picked.

Our neighbors told us that the growing season was short. The seeds we planted seemed to know it. They grew rapidly. Gathering crisp vegetables from the garden is pure pleasure compared to collecting them in a grocery cart at a super-market. And they have a flavor that I supposed had vanished with my childhood.

The familiar things I find at the ranch are electricity and butane and the appliances they operate. This permits us to cling to a way of life that we have come to expect. The things that are new, and a never-ending delight are mostly the native gifts of this country.

I get a nostalgic feeling for the frontier days in the rustic, pinelined lean-to. On cool days I fill the woodbox from the grove and make a fire in the stove just for the sound of it, the smell of it, and the feel of it. In this room I can enjoy the patter of the rain on the roof. The rest of the house is as modern as today.

There is a well in the flower garden. The water is cold and sparkling and good. So different from the treated water we were used to in the city. An electric pump delivers it into the house.

Outdoors beckons every day. I walk through the meadow helping my husband move the cows from one pasture to another, or I go into the grove for an armful of wood, or down to the garden to water or hoe. I thrill to the feel of the wind, the rain, and the sun. My wanderlust feet take me along the creek and I see the water dimple where a small fish snatches a bug from the surface. I stop to eat a handful of serviceberries, remembering from reading history that these berries supplied nourishment for the Indians and early pioneers. Wild fruits and flowers flourish along the fence line, the creek, and through the meadow. As I walk I find little bluebells, thistles with purple pom-poms, wild geraniums, larkspurs, poppies, and daisies. Mushrooms grow from a vivid red color to a startling white.

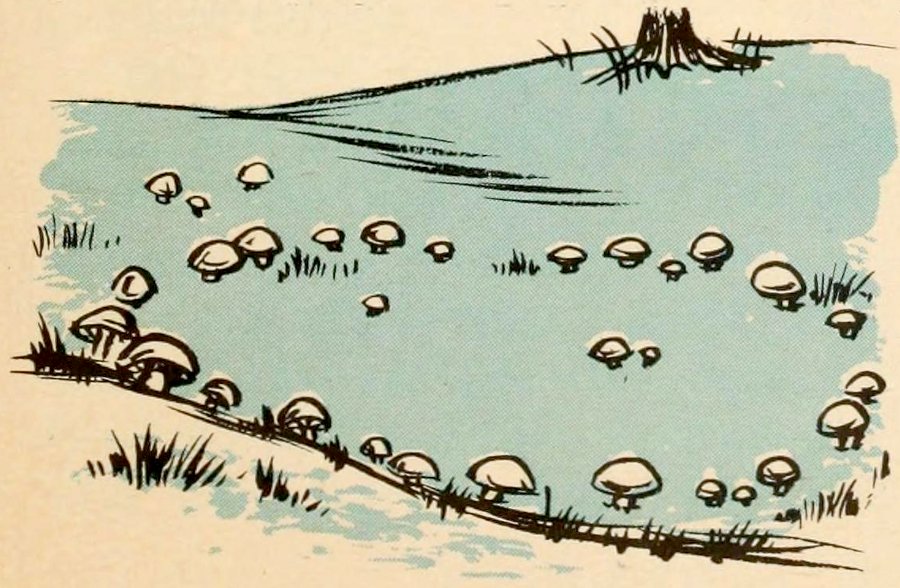

It is here that I saw my first fairy ring. It was just a few days after a rain. From the house I could see the luminous white circle down where the meadow dips the lowest. It was early evening. The sun had just set. I climbed over the corral fence and fairly flew down the slope. There they were, phosphorescent mushrooms, making a mystical fairy ring in the dark grass.

One night when the air was warm and still, I looked out our window to see hungry red flames leaping up behind the trees the other side of our grain field. "It is all right," my husband said. "The neighbors are burning brush." We drove over to their ranch to watch the roaring blaze. Where else, but in the open country could a fire a quarter of a mile long be a spectacle of beauty instead of a tragedy?

There isn't a great deal of wild life on the ranch. There were deer tracks across the summer fallow one morning. We see an occasional pheasant in the field, and ducks stop briefly in the little pools along the creek. Squirrels chatter in the trees and crows hold conventions in the grove and the meadow. Once in awhile we see a skunk scurrying for cover.

Away from the city lights, we have re-discovered what a show the night sky has to offer. Once more we enjoy the brilliance of stars and moon and the lightning when there is a storm. Night skies in the city are pale above the street lights and flashing neon signs. The only lights we see here at night, aside from those in the heavens, are the distant mellow lights from our neighbors' homes that reach out across our meadow like a warm handclasp.

Farm folks are friendly. Our neighbors run in with a little jar of chokecherry jelly or a picking of beans. They help us harvest our hay and grain, and doctor a calf when trouble comes.

The ranch women in our neighborhood milk cows, run the hay baler, and drive tractor. They can talk wheat varieties, acreage production and market prices. They keep their hair styled, their nails manicured, and keep themselves trim. They are active in politics and civic affairs. The school bus picks their children up at the gates.

We are only three miles from a hospital and a super-market. We are less than an hour's drive from the city. Our roads are good, and the mail man delivers our mail each day.

The glamor of the city is ours to enjoy when we wish, and yet we are out under a wide expanse of sky surrounded by stretches of fields and forest-fringed meadows. We enjoy again the drama of the sunrise and the sunset.

I am as filled with wonder as though I had just discovered America.